Members of our engagement team have been taking a look at the lives of three Staffordshire Women for Women’s History Month.

Mabel Layng

Community History Development Officer Hannah takes a look at the artist Mabel Layng.

Mabel Layng (1881-1937), born in Macclesfield, moved to Stafford early in her life. She was around two years old when her father took up the post of Headmaster at Kind Edward VI school in Stafford after the death of his wife (Mabel and her sister’s mother). She remained in Staffordshire until 1902, when she left to study at St John’s Wood Art School in North London, and later the London School of Art in Kensington. Layng’s work was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art in 1916, and she would continue to exhibit at the RAA until 1928. Her works were also exhibited at the Paris Salon, Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts, Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and Women’s International Art Club, to name a selection. A number of her paintings are housed in Staffordshire Archives and Heritage’s fine art collection.

There is no record of Layng marrying, something relatively unique for her time, and supported herself through her career as an artist. It must be acknowledged her middle-class status went some way to facilitating her career, and thereby her ability to live as a single woman. She lived with her sister in Ealing from 1914 until the closing years of her life when she resided at Camberwell House, a private psychiatric facility, passing away aged 56.

Turning now to her canon of work, what is striking of Layng’s portraits is her commitment to the female subject: capturing, embracing, and celebrating female existence. Though men feature in the artwork, they are often on the periphery, in the background and, almost without fail, outnumbered by female subjects. Women are the owners of Layng’s canvas space. Yet, they are not ‘remarkable’ women: women of remarkable status, of remarkable beauty, of remarkable acclaim. They are the quotidian woman and there in, for Layng and viewers alike, lies their intrigue.

The aspect of Layng’s paintings I enjoy most is her expression of female companionship and bonded community, so let’s take a look …

‘Under the Trees‘ is a beautifully serene depiction of female friendship. At ease in one another’s presence, three young women group under a tree in various states of recline. The women appear not to be in conversation, perhaps a moment of comfortable silence whilst enjoying one another’s company. The tranquillity of expression in this image is perhaps incidental, as Layng’s style typically depicts her subjects without overt emotion, however it lends itself wonderfully to this calm, almost comforting, scene grounded in female companionship.

We see a similar theme emerge in ‘At the Greengrocers’ and ‘Bread Shop’ (1915-1920). The female subjects of these paintings appear older than those of Under the Trees, with accompanying babes-in-arms suggesting they have taken on another life stage, which, coupled with the paintings’ grocery-based settings, seemingly centres around motherhood and domesticity. It is interesting ‘traditional’ maternal dynamics feature fairly regularly in Layng’s paintings, considering she herself followed a less prescriptive lifestyle. Why this may be can be left to your interpretation, such is the nature of art. Whether one wants to adopt a perspective of domesticity limiting women’s scope or a more revisionist-feminist approach that a semblance of power could be obtained through the household economy, what can be true for both, as shown by Layng, is that the domestic sphere provided opportunity for female bonding through routine, shared experience, such as a trip to the shops. We can pause and think what these women may have been discussing, what aspects of their lives were they sharing with one another and bonding over.

To discover more of Mabel Layng’s work, including more scenes of the ‘quotidian woman’, visit our Staffordshire Pasttrack website or, in the future, the Staffordshire History Centre.

Mary Blagg

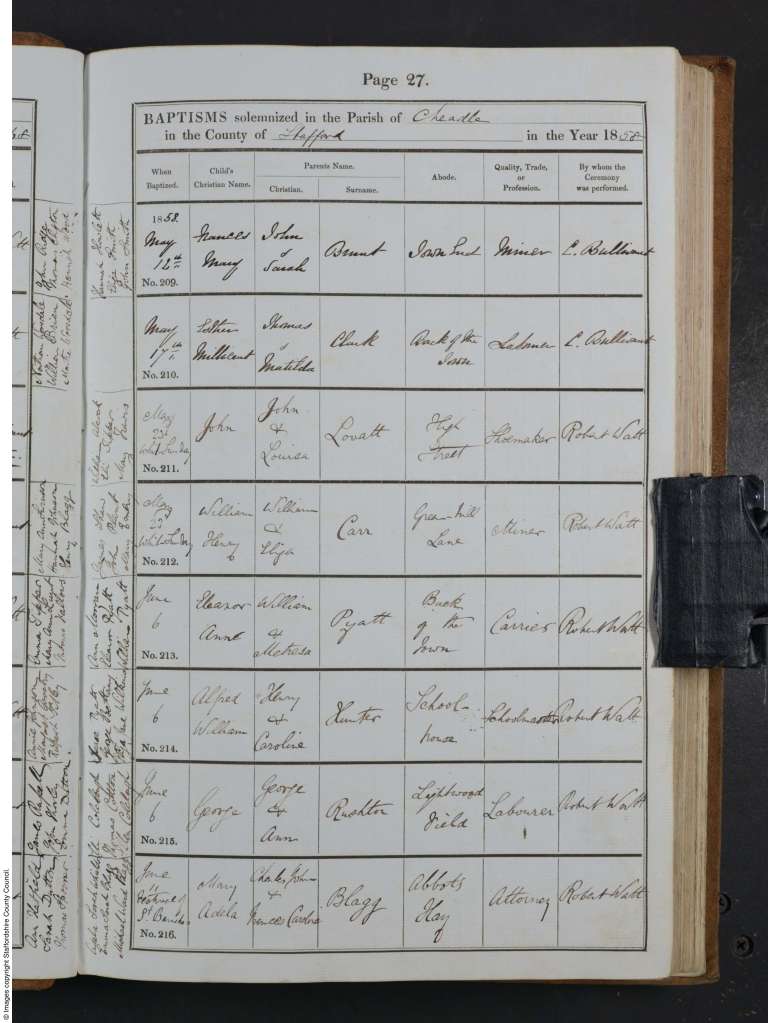

Learning Officer Lizzie explores the work of Cheadle born Mary Blagg.

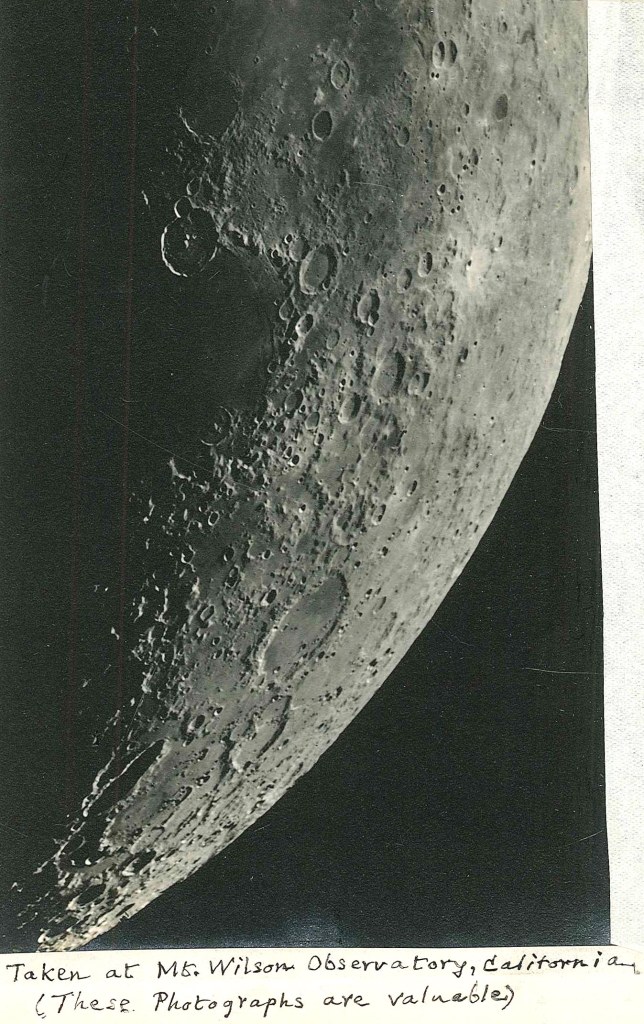

Mary Adela Blagg was born in Cheadle in 1858, the eldest of twelve children. Her solicitor father’s salary was able to support the large family, and Mary took full advantage of the opportunities afforded by the family’s middle-class wealth: she painstakingly taught herself advanced mathematics at an early age by borrowing her brother’s textbooks, and went on to study algebra formally. She became interested in astronomy when she met Joseph Hardcastle, John Herschel’s grandson, and set her mind to selenography: the study of the moon’s surface.

Specifically, Mary began singlehandedly organising the lunar nomenclature used across the world, eliminating discrepancies, and creating a standardised naming system for the moon’s mountains, valleys and craters. Alongside revolutionising an entire field of study, Mary wrote ten articles on the properties of variable stars and investigated Bode’s Law, correcting and removing a major flaw (the formula predicts distance between planets and is used by astronomers today). She was admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society as a fellow in 1916: she was the first woman to be elected, alongside four other female scientists who were elected simultaneously.

Upon the outbreak of WW1 she cared for Belgian refugee children and continued her teaching at the Cheadle Sunday School. Her work whipping the moon’s landmarks into shape would continue into her late 70s, just a few years before her death in 1944. Mary never moved from her hometown Cheadle and her obituary paints a quiet picture, describing her as ‘modest and retiring (…) in fact very much of a recluse’. Despite her relative anonymity, her legacy lives on: the Blagg lunar crater is named in her honour, and in March 2023 a minor planet in the asteroid belt was designated 50753 Maryblagg. 150 years after she began to teach herself mathematics using her brother’s textbooks, Mary’s name is in the stars.

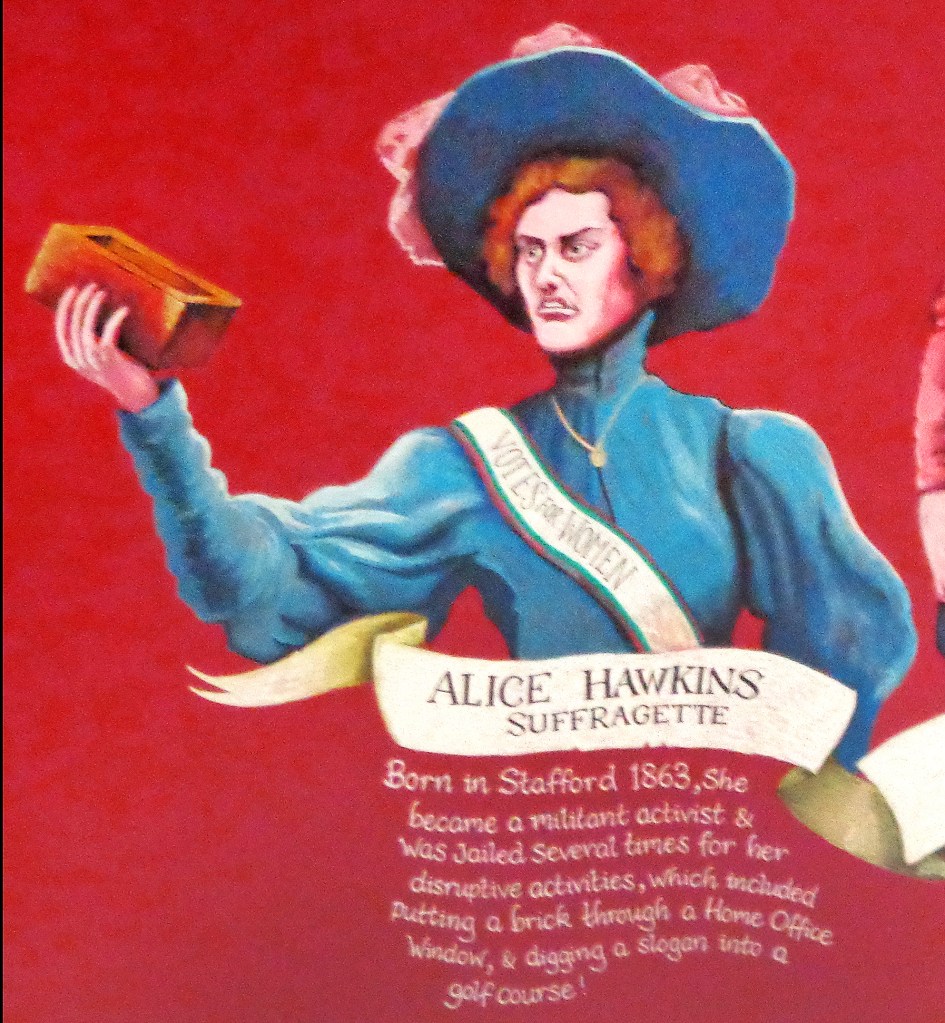

Alice Hawkins

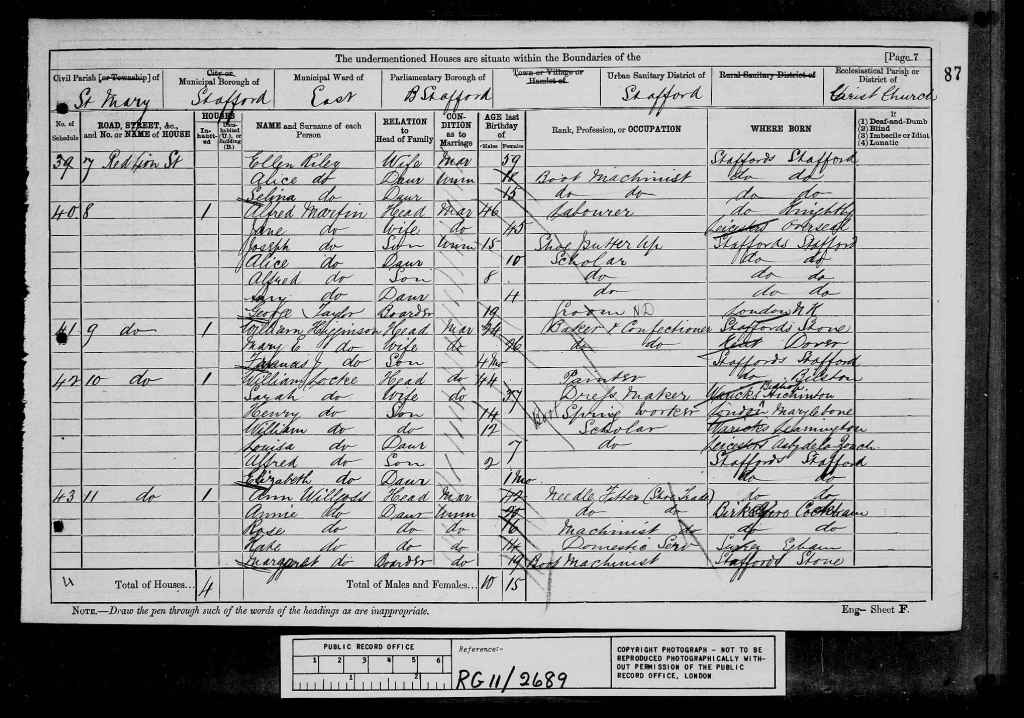

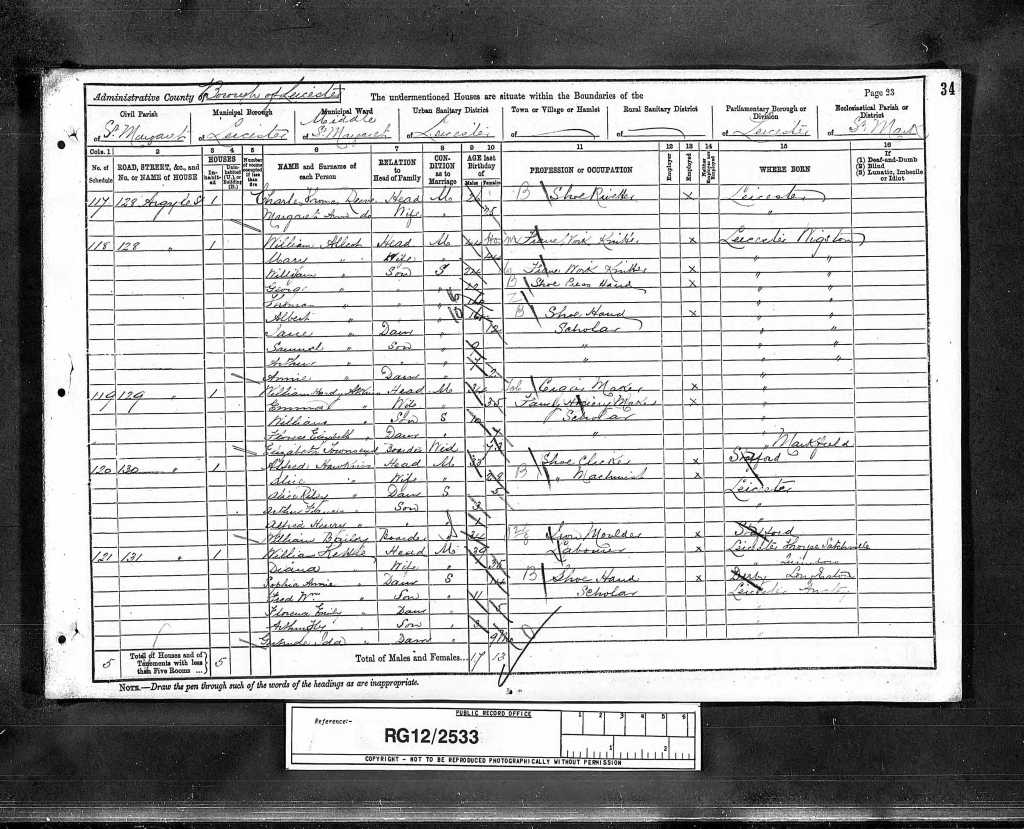

Engagement & Access Manager Sarah uses census data to consider the Staffordshire roots of a pioneering Suffragette.

Alice Hawkins is today remembered as the leading figure amongst Leicester suffragettes, one of the few prominent working class women in the movement and a militant campaigner for equality. Whilst noted for her links to the East Midlands she actually spent her early years in Stafford.

Alice was born in Stafford in 1863 to Henry and Ellen Riley. In 1871 the family were living at number 4 Red Lion Street, close to Stafford Prison and St. George’s asylum. Alice is listed as still in school and her older siblings are working as shoe factory machinists and as a leather cutter. Interestingly her father is not listed as shoemaker but as “assistant keeper of the town hall” – this unusual occupation has been queried by the enumerator (and as Stafford had both a shire and borough but not a town hall it seems a very strange description!)

By 1881 the census indicates that Alice is unmarried and still living with her parents and one younger sister at number 7 Red Lion Street. Her father’s occupation is night watchman (possibly at Stafford Prison) and Alice and her younger sister Selina are listed as boot machinists.

Some sources describe Alice as starting work at Equity shoes in Leicester at age 13; could the sisters have just been visiting their parents on the day of the census or has it been forgotten that young Alice first worked in the Stafford shoe industry before moving to Leicester? If Alice’s desire for radical change was formed by her early workplace experience, it could have been time in a Stafford factory that led to a lifetime of fighting for rights.

The 1891 census shows Alice now married to Alfred Hawkins, who was also born in Stafford, and living in Leicester. Alfred and Alice are both working in the shoe industry and have three young children.

(There is a slight age discrepancy for Alfred that makes it difficult to trace his early years in Staffordshire – there are two possible Alfred Hawkins on the 1871 census in Stafford and none in 1881. We don’t hold any baptism records for either Alice & Alfred in our archives.)

The 1891 census also shows that Alice’s maiden name lived on through the middle name of her daughter, Alice Riley Hawkins, who was born in 1885.

Alice and Alfred shared the same political beliefs and they both campaigned for political, social and working equality. In her campaigning for the vote Alice went to prison five times and Alfred was awarded compensation for being ejected from a political meeting when he challenged the ban on women attending. It must have taken an incredible amount of bravery, sacrifice and determination to become a leader in the campaign for electoral equality as a working mother.

Following the end of active suffragette campaigning in 1914 Alice continued to campaign for workers rights. She didn’t actually qualify to vote until 1928, and later in life it is recorded that she urged her family to use their right to vote that she had suffered to win. When she died in 1946 it was front page news in Leicester; her memorial stone reads ‘a sister of freedom’.

Alice was celebrated in 2018 with a statue in the place where she used to address crowds, and her suffragette memorabilia was displayed in an exhibition at the houses of parliament as part of the Vote 100 commemoration.

Sadly the 19th Century houses on Red Lion Street no longer exist, so there is nowhere to place a plaque in her birth town, but you might spot Alice in Stafford today whilst stopping for coffee or cake. She is shown in all her true militant strength in a coffee shop mural on Greengate street – I hope you take a look and take a moment to remember our Stafford Suffragette if you are passing; I will certainly say a silent thank you to Alice the next time I’m at a polling station in Stafford.

Alice’s family are proud of their great grandmother and have a website dedicated to her achievements which you can find here: Alice Hawkins and The National Archives explored Alfred’s support and Alice’s written testimony in this blog: Alice Hawkins, suffragette and working woman

Leave a comment