Blackadder: Baldrick, I’ve always been meaning to ask, do you have any ambitions in life apart from the

acquisition of turnips?

Baldrick: Er, no.

Blackadder: So what would you do if I gave you a thousand pounds?

Baldrick : I’d get a little turnip of my own.

Blackadder: So what would you do if I gave you a million pounds?

Baldrick: Oh that’s different, I’d get a great big turnip in the country.

Blackadder, Series 3, Episode 1, ‘Dish and Dishonesty’

If only Baldrick had been reading his Lichfield Mercury on Friday 6th October 1815. If he had, he would have seen on page three the following advert placed by Mr Watton, a local brewer: “TURNIPS – To be LET, Five Acres of Capital TURNIPS, on dry, sound land”. Although no further information is provided, I assume this would have cost less than the million pounds Baldrick was willing to spend on his great big turnip in the country.

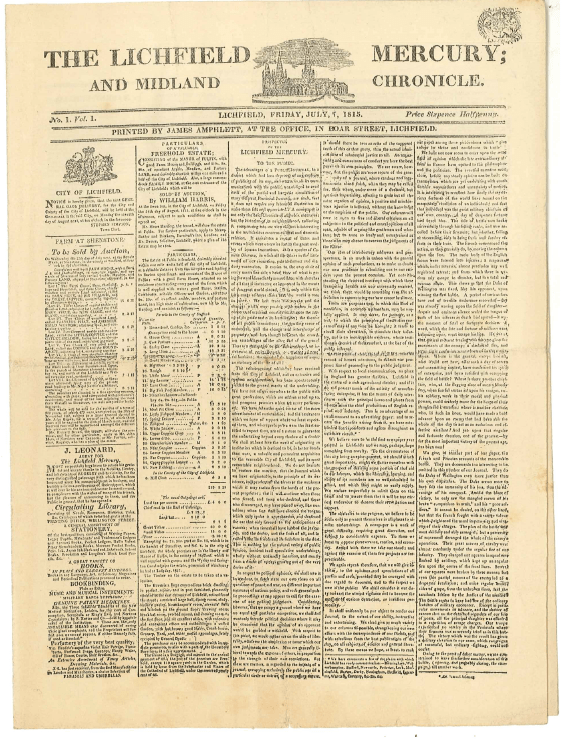

The first edition of the Lichfield Mercury and Midland Chronicle, as it was known then, was published on Friday 7th July 1815 by James Amphlett from his offices on Boar Street. In it, Amphlett promised the residents of Lichfield, which had been “deprived of any medium of publicity of its own”, that his newspaper would be “a valuable and permanent acquisition to the venerable City of Lichfield, and its most respectable neighbourhood”. For the price of sixpence halfpenny (which quickly rose to seven), subscribers could read articles and announcements about important goings on in the area and further afield. Readers were kept abreast of local births, marriages, and deaths; bankruptcies; the market price of wheat; upcoming auctions; details of the Agricultural Society’s next meeting; and the latest fashion trends.

Public submissions to the Mercury came in the form of poetry, such as ‘The Soliloquy of Bonaparte’, ‘An Invocation to Poverty’, and ‘Fretfulness – An Ode’. There were also letters to the editor, although these were not always complimentary. One disgruntled reader complained about “an erroneous statement of the accident that happened to the horse industry, on Lichfield Race Course”, calling the journalist who wrote the piece “an amateur” whose “statement is very incorrect, and his opinion of very little value”. Ouch. Job advertisements were common, although they often contained language that would not pass muster today. One such advert came from the North Staffordshire Infirmary, which was seeking “an active, steady, middle aged WOMAN, unincumbered with a family” to become the new matron.

Several pieces in the Mercury summarised excerpts from other contemporary newspapers, such as one article declaring that “a Frankfort Paper, received yesterday, mentions ‘that many old chateaus near Madrid had been fitted up as prisons’”. An extract copied straight from The Examiner, meanwhile, complained that the Prussians “have nothing on which to value themselves as a people. They have no literature, no liberty, [and] no beauty of soil”. I wonder to what extent Mercury readers agreed with this sentiment.

According to Amphlett, “a newspaper is not only the brief Chronicle of all public measures; but the historian of its neighbourhood, collecting & compressing into one view all that is interesting in the multifarious concerns of local and domestic relation”. You can read this chronicle for yourself at the History Access Point, where we have microfilm versions of the Mercury from 1815 until 2008. Lichfield HAP is located on the first floor of the Hub at St Mary’s, we are open Tuesday-Saturday, with our team of volunteers on hand to answer any queries you may have on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. For more information and our opening times visit our web page or blog page.

Alex – HAP Volunteer

Leave a comment